How Socialist was the New Deal?

Socialists supported it and was a fundamental break with the capitalist state that preceded it - but compromises with Jim Crow limited its full radicalism

Earlier entries in this series on the relationship of American liberalism and socialism:

AOC, Bernie and Zohran are Socialists – but so are Kamala and Joe

The Democratic Party is as Socialist as European Social Democratic Parties

In a fundamental way, the New Deal reflected the beginnings of a socialist break with the laissez faire economy that proceeded it. While FDR was not a self-identified socialist, as this piece will detail, he embraced radical new ideas and policies, including Keynesianism, that represented that break with laissez-faire and led opponents and even the general public to label him and New Deal policies as socialist.

And if personnel is policy, FDR appointed many socialists to important positions, including his Frances Perkins as his Labor Secretary and CIO leader Sidney Hillman to the crucial War Labor Board, reflecting his embrace of people with socialist ideas to staff his presidency. Broad socialist forces in American society also embraced this radical shift in the Democratic Party as groups ranging from the Communist Party to large chunks of the Socialist Party, as well as socialist-and -communist leaders of the rising industrial unions in the CIO, supported FDR’s reelection in 1936.

New Deal policies embraced by the New Deal represented a critical break from the past in building worker power, building federally funded social welfare spending, expanding the administrative state, taxing the wealthy, and embracing government management of the overall economy via Keynesian economics.

In the end, the clearest limits on the socialist radicalism of the New Deal was its fatal compromise with Jim Crow, which would lead over time to the weakening of the labor movement and seed the rise of the racist New Right and then the Trumpist MAGA movement of today. But the Democratic Party would be set on a new course of increasingly more socialist-oriented policies as the decades advanced.

Was FDR Himself a Socialist?

While never self-identifying as a socialist, Roosevelt’s willingness to experiment sprang partly from biography. Patrician breeding gave him a front‑row seat on how concentrated wealth behaves; polio, by hammering his body, sharpened his empathy for the broken economy he inherited. In private, aides noted that he was “open to radical ideas” precisely because he assumed the old order had failed.

That openness burst into the public square during the 1936 re‑election campaign. Speaking in Madison Square Garden, FDR thundered that “business and financial monopoly, speculation, reckless banking” were his sworn enemies and that he welcomed their hate. The line was less a rhetorical flourish than a declaration that the era of polite deference to Wall Street was over.

This overall commitment by government as the key defender of the public against economic danger was ratified by Roosevelt in his 1941 '“Four Freedoms” speech where along with traditional freedoms of speech and religion, he highlighted the goal of a world founded on the “freedom from fear” and the “freedom from want”, both of which demanded active government, including a guarantee of “Jobs for those who can work” and “The ending of special privilege for the few.”

This was a radical shift from the policy of the past, embodied in Herbert Hoover’s argument in 1928 that government should promote an “American system of rugged individualism” and be no more than “an umpire instead of a player in the economic game.” The country’s old guard saw the whole New Deal as betraying this American capitalist system of “rugged individualism” that had previously been a bipartisan consensus. The Liberty League—financed by DuPont heirs and fronted by 1924 Democratic nominees John W Davis and 1928 Democratic nominee Al Smith—broadcast that Roosevelt’s platform was “little different” from that of the Socialist Party. That the previous Democratic leadership was now aligned with the Republican Party sent a powerful message of FDR’s challenge to that earlier bipartisan deference to corporate interests.

Walter Lippmann, high priest of inter‑war liberalism, darkly warned that the New Deal heralded “gradual collectivism” and the selective doling out of privilege, a critique recounted by Zachary Carter in The Price of Peace. Laissez‑faire orthodoxy saw any kind of minimum wages, guaranteed union rights, or insured deposits as indistinguishable from socialism seeing them as a fundamental break .

Keynesian economics proved the sharpest rupture. Roosevelt never read The General Theory itself, but he grasped its political meaning: when private spending freezes, public spending must thaw it. That insight set him apart not only from American conservatives but from many European socialists. Britain’s Labour prime minister Ramsay MacDonald, ostensibly a socialist, imposed austerity in 1931 under City of London pressure, prompting Keynes to call the cuts “one of the most wrong and foolish things” Parliament had ever done. Roosevelt, by contrast, poured billions into the WPA, the Public Works Administration, and relief grants—accepting deficits as the price of jobs. It was an ideological jailbreak: Washington assumed responsibility for managing aggregate demand, a task classical economists said lay beyond the state’s remit.

The public noticed the transformation. A 1949 nationwide poll found that 51 percent of Americans agreed with the statement “We have socialism in the U.S. today,” only 43 percent demurring. Harry Truman, campaigning in 1952, shrugged that every New Deal and Fair Deal measure—rural electrification, Social Security, price supports—had been tarred as socialism, and that he was proud to keep wearing the smear. The label had migrated from fringe insult to a back‑handed badge of popular reform.

When Personnel Is Policy: The Socialist Core of Roosevelt’s Brain Trust

Roosevelt may have joked that he was “a little left of center, maybe,” but the résumés stacked on his desk told a story of a Cabinet and sub-Cabinet crowded with veterans of the Socialist Party, the Communist underground, and campus circles where “production for use” was dinner-table doctrine. The New Deal labor and social policies flowed from a talent pool steeped in socialist aspiration.

Frances Perkins, the first female Cabinet member in history, was officially a Democrat yet carried many of her old Socialist-Party convictions into the Labor Department, shepherding the Fair Labor Standards Act and Social Security with the fervor of someone who once handed out Debs tracts in Philadelphia.

Sidney Hillman, a former top Socialist Party leader who was one of the key founders of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), was appointed by Roosevelt to the War Production Board, which had the lead role in organizing industry during World War II and was seen as such a key advisor to FDR that people were reportedly told to “clear it with Sidney” before Truman could be nominated as Vice President in 1944. Their partnership embedded collective-bargaining rights and industrial planning at the very heart of wartime governance.

Economists Mary Dublin Keyserling and husband Leon Keyserling drafted wage-hour rules, public-housing statutes, and—later—full-employment bills for FDR. Both called themselves “democratic socialists” in the 1930s; both treated deficits not as sins but as investments in social citizenship. Leon’s housing blueprints aimed to “socialize economic power through democratic means.”

Catherine Bauer Wurster, Director of Research & Information at the U.S. Housing Authority, imported European “Red Vienna” ideas, insisting the state must “compete directly with speculative landlords” and helped design the Wagner-Steagall Act for public housing.

Wilbur Cohen, who was one of the first appointees to the Social Security Board, called pensions and unemployment insurance “first steps toward American social democracy.”

Communist Party members Lee Pressman, General Counsel at the Works Progress Administration, John Abt, Assistant General Counsel at the WPA, and Nathan Witt at the National Labor Relations Board embedded themselves in the Agricultural Adjustment Administration and the National Labor Relations Board, saw supporting FDR policy as an outgrowth of popular front socialist organizing.

Roosevelt’s hiring ledger leaves little doubt: he chose multiple advisers whose life work was taming or toppling the profit system. Their previous socialist passions —industrial union rights, public housing, Social Security, deficit-financed full employment—mirrored the key outcomes that FDR’s administration would implement.

Socialist Organizations Saw the New Deal as Advancing Socialism

The Socialist Party and the Communist Party, which had split from Debs’ party after the Russian Revolution, had both long preached that real change required shunning both bourgeois parties. Early on, Socialists opposed FDR and the Communist Party USA dismissed the New Deal as “social‑fascism.” But within a few years, much of America’s radical left performed an electoral about‑face that would bind it to the Democratic Party in an uneasy but ongoing alliance— and by November 1936 these currents were mobilizing volunteers, money and arguments to re‑elect Franklin D. Roosevelt. Mass institutions they controlled—front organizations, fusion ballot lines and union political departments—channeled hundreds of thousands of votes into the New Deal coalition.

The Communist pivot was part of a global change in reaction to Hitler where after 1935, CPUSA leaders began supporting a Popular Front against fascism that largely supported FDR’s New Deal Democrats. General Secretary Earl Browder complied, but the decisive actors were the Party’s front groups. The Communist‑led Workers Alliance of America mobilized relief workers, while the National Negro Congress registered Black sharecroppers and campaigned against the poll tax, openly endorsing the President.

While the CPUSA ran a nominal campaign for President in 1936, most of their energy went into supporting FDR’s reelection. Despite Party membership exploding from roughly 13 000 in 1932 to about 40 000 in 1936, votes for the Communist ticket fell from 100 990 votes in 1932 to 79 306 votes in 1936—evidence that tens of thousands of previous Communist supporters cast Democratic ballots.

Socialists faced the same crossroads. While party leader Norman Thomas upheld electoral independence, Socialist leaders and union heads Sidney Hillman and David Dubinsky judged that supporting FDR and the New Deal would be the best route to furthering socialist and labor goals. In June 1936 their faction split from the Socialist Party and founded the American Labor Party, a fusion line that carried Roosevelt’s name in New York and delivered nearly half a million votes to FDR on a socialist political line.

Even more decisively, the new Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), whose union leadership were overwhelmingly various shades of socialist or communist, built Labor’s Non‑Partisan League (LNPL), By November it claimed nearly four million union pledge cards and distributed six million leaflets urging workers to “Vote Roosevelt, Vote Union.” LNPL organizers placed pay‑envelope leaflets in Pittsburgh steel mills, ran phone banks in Chicago packinghouses and staged plant‑gate parades in Flint, linking union recognition directly to New Deal ballots. Subsequent surveys showed roughly two‑thirds of union households voting Democratic—a habit born in the 1936 drive.

Republicans and most of the socialist left would agree by 1936 that FDR was advancing socialist goals- and that left along with the labor movement would join the Democratic coalition, with only a small sectarian left fringe dissenting in third party protest - a political alignment that has, with consistent grumbling on the left, largely persisted for the last ninety years.

How the New Deal Broke with Laissez Faire Capitalism

Ultimately, you have to judge the New Deal on how much it fundamentally altered the capitalist system that preceded it and shifted power to working people - and its break with the past was pretty fundamental on multiple fronts.

Expanded Labor Power: At its heart, what people think of as the New Deal - the rise of a working class rich enough to afford their own homes and live a good life with rising pay - was a product of the legal empowerment of the labor movement. The passage of the National Labor Relations Act, the so-called Wagner Act, in 1935 is helped pave the way for a surge of new union organizing that increased the number of union members in the nation from just 3.5 million in 1935 to 14.3 million in 1945 - and would peak at a third of the industrial workforce in unions by the early 1950s. The result, as this graphic by the Economic Policy Institute highlights, was that economic inequality decreased almost exactly in tandem with the rise in union density (and would increase decades later as union power slid, particularly under Reagan).

Beginnings of a Welfare State: What is not fully recognized is that there really was essentially no real federal spending on social programs to help working people before the New Deal, only 0.6% of GDP in 1930. The New Deal as you can see from this graph (a version of which was in the last in this series) was the inflection point when social spending began trending upwards for the first time in out history. While spending has significantly increased since then, it was a fundamental shift to legitimize social spending as a role for the federal government.

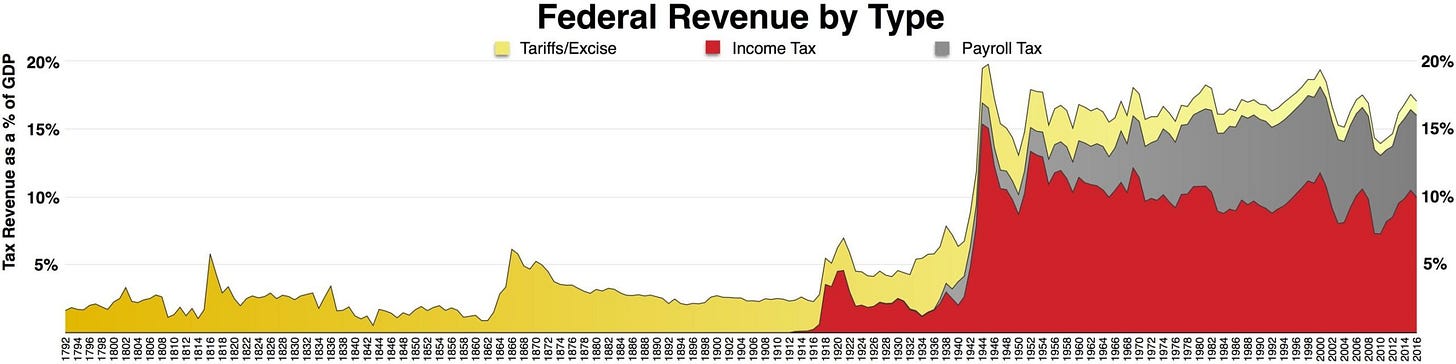

Progressive Income Taxes Became the Main Staple of Federal Revenue: While the income tax was first introduced and played an important role in funding World War I, tariffs and excise taxes on products like alcohol — all of which were regressive taxes on working people — were the staple of federal funding until the New Deal and World War II in particular made the income tax the main source of federal funding. And it was only an expanded income tax that would allow the large growth in social spending in the postwar era.

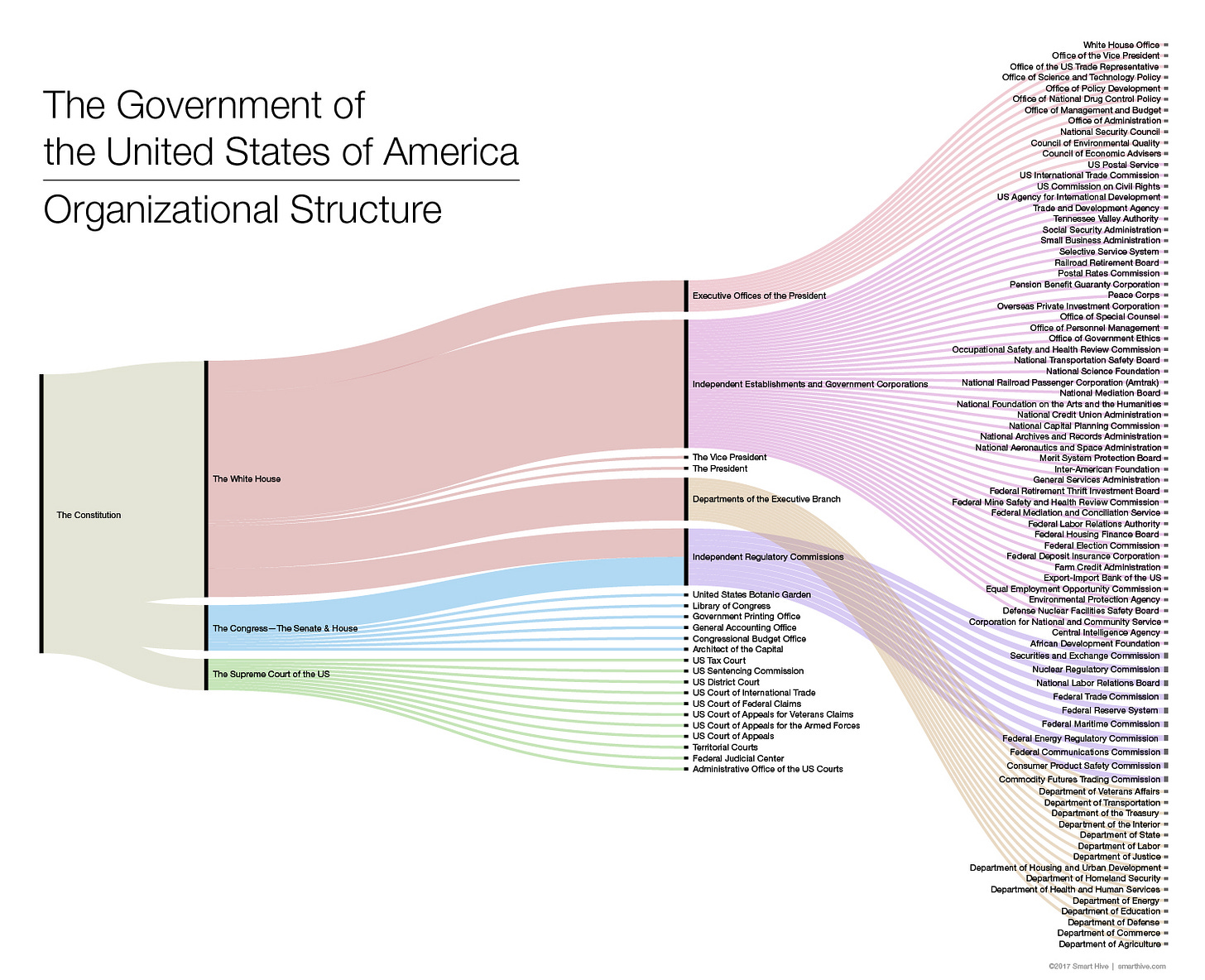

Creation of the Administrative State: What the New Deal also brought to life was the myriad “alphabet” of new agencies helping to guide the economy, ranging from the Federal Communications Commission to the National Labor Relations Board.

In many ways, we take them so much for granted now, that their absence- as Trump brings a wrecking ball to them, gutting corporate crime enforcement, disabling labor rights and endangering the safety of the public by crippling regulatory agencies- is a shocking reminder of the wild west of absolutely unrestrained corporate power that existed before their creation.

Keynesian Control of the Economy: Finally, the embrace of Keynesian economics - along with FDR abandoning the gold standard and devaluing the dollar - was a declaration that it was in the power and responsibility of government to fight unemployment and control the economy in a systematic way.

Keynes’s himself saw the adoption of active management of fiscal policy a a shift to socialism: As he said in 1939:

“The question is whether we are prepared to move out of the nineteenth-century laissez-faire state into an era of liberal socialism, by which I mean a system where we can act as an organised community for common purposes and to promote social and economic justice, whilst respecting and protecting the individual—his freedom of choice, his faith, his mind and its expression, his enterprise and his property.”

Again, this was a fundamental break with the past that we so take for granted that we barely can imagine a time when the government would do nothing for years on end as mass unemployment engulfed the nation, as it did regularly in the 19th and early 20th century until the New Deal created public demand going forward for government to act.

The Racist Compromises of the New Deal that Took Decades for Modern Democrats to Address

If there is any reason to qualify the radicalism of the New Deal it’s that its socialistic impacts largely bypassed the South, particularly the African American population there, as FDR and northern Democrats were forced to defer to the Jim Crow political demands of southern Democrats. Author Ira Katznelson in his excellent Fear Itself: The New Deal and the Origins of Our Time referred to the “southern cage” where the further south one went, the smaller the impact of the New Deal. Both the minimum wage and the National Labor Relations Act refused labor rights to agricultural and domestic workers - the prime employment of African American in the South - and jobs in programs like the WPA ended up controlled by local politicians who in the south ensured those jobs went disproportionately to the white unemployed.

What this meant is that if there was a new regime of social democratic and even socialist policies for people of all races in the North - and Northern blacks benefited tremendously from the New Deal - there was still left a core of pure unregulated racist capitalist exploitation in the South. And any threat to reverse that was met by southern Democrats switching political sides and allying with Republicans to reverse New Deal programs.

The most dramatic example of this was when CIO unions began planning a union organizing drive in the South after World War II. In response, twelve years after the Wagner Act was enacted with nearly unanimous support from southern Democrats, almost every single southern Democrat, including future President Lyndon Baines Johnson, sided with Republicans to pass the anti-union Taft-Hartley Act in 1947 over Truman’s veto - a bill that would create a slow leak in the power of unions that would lead over time to their massive decline in future decades. Similar losses would be suffered repeatedly in other areas, including many southern Democrats supporting Ronald Reagan’s assault on the welfare state during his Presidency.

Despite these threats and betrayals, northern Democrats eventually forced through civil rights legislation and changes in other laws that extended protections to southern black and other non-white workers and families- and even as Dixiecrats became Republicans, you also had a new crop of progressive southern Democrats emerge who are now in many cases as strongly committed to labor rights and other social democratic policies as their northern counterparts. What this meant was that by the Biden administration, when a new pro-labor law the PRO-ACT came to a vote, not a single Democrat voted no in the Senate and only one in the House voted no, reflecting a sea-change in the party, particularly among southern members, since the 1947 Taft-Hartley vote.

The frustrations of the filibuster remain but with this deeper commitment to justice for all Americans built into the DNA of the party, there is the promise of more far-reaching policies if the Democrats can finally abolish the filibuster and act on the core promises of radical change that the New Deal began.