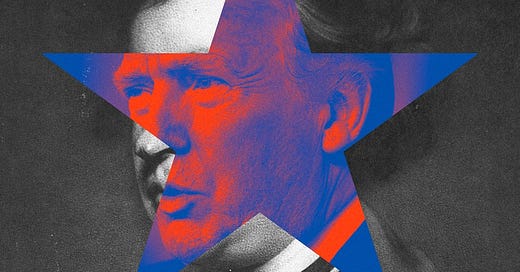

David Brooks Details the Death of American Conservatism - If It Ever Existed

Progressives should embrace this analysis from within of the intellectual decay of the GOP

David Brooks is an odd figure in the intellectual firmament of US punditry, a writer often reviled on the left for his apologies for Republican policy but also on the right at times for his squishiness in that defense.

In this Atlantic essay, “WHAT HAPPENED TO AMERICAN CONSERVATISM?”, Brooks basically throws in the towel and, while not completely renouncing his past apologies for Republican politics, admits his more optimistic hopes for American conservatism were largely blinded to the rot within.

If not as blunt as former GOP campaign strategist Stuart Stevens’ It Was All a Lie: How the Republican Party Became Donald Trump, Brooks largely comes to the same conclusion.

Brooks warms up with his stories of his infatuation with Edmund Burke and the broader conservative tradition of embracing gradualism and political modesty in the face of modern technocratic policy upheavals. But he eventually cuts to the chase of why Trump is the inherent byproduct of American conservatism, not its betrayal.

Conservatism makes sense only when it is trying to preserve social conditions that are basically healthy. America’s racial arrangements are fundamentally unjust. To be conservative on racial matters is a moral crime.

Brooks touches on exactly why we have the moral panic we see on the Right coded as attacks on “Critical Race Theory.” To admit that racism was at the root of many American institutions is to admit conserving those institutions is neither admirable nor tenable morally. Censorship of that history is the only option to maintain the viability of conservative ideology.

While not quite as frank as Stuart Stevens in seeing racism was the core of Republican policy long before Trump, Brooks admits that in the 1980s, among the conservative intelligentsia “racial issues were generally overlooked and the GOP’s flirtation with racist dog whistles was casually tolerated.”

When it was not embracing that moral crime of racism, Brooks says, at best, American conservatives were ignoring that reality. “When you ignore a cancer, it tends to metastasize.” Ergo Trump.

And the frantic nationalism of the Trumpist Right is a byproduct of the lazy conservative embrace of the past as explaining American economic dominance in the 20th century. When communities found themselves left behind due to corporate greed and globalism’s disruptions, a nationalism built on the theme that “Evil outsiders are coming to get us” is all American conservatism had to explain those failures. In denial of both the racism at the heart of many American institutions and why those institutions failed so many communities, “The Trumpian cause is held together by hatred of the Other.”

So much for Brooks’s diagnosis of the racist contradictions that ultimately laid low the conservative movement in America.

What I do find worth highlighting as well is the parts of conservative thought that attracted Brooks in the first place - since recognizing how those adapt to progressive politics is important to understanding debates on the left as well. And since Brooks himself ends his essay by formally aligning himself on the left, if gingerly “on the rightward edge of the leftward tendency,” that Burkean tendency is likely to only grow in importance in internal progressive debates.

And I don’t think it will be an unhealthy addition.

Brooks begins his essay by arguing his shift to the Right began with his rejection of the results of urban planning from the mid-20th century:

Cabrini-Green and the Robert Taylor Homes, which had been built with the best of intentions but had become nightmares. The urban planners who designed those projects thought they could improve lives by replacing ramshackle old neighborhoods with a series of neatly ordered high-rises.

But, as the sociologist Richard Sennett, who lived in part of the Cabrini-Green complex as a child, noted, the planners never really consulted the residents themselves. They disrespected the residents by turning them into unseen, passive spectators of their own lives. By the time I encountered the projects they were national symbols of urban decay.

As his quoting of Richard Sennett emphasizes, there are many on the left who reject the results of urban planning as a particular failure of technocratic politics in postwar America - and hardly representative of the ideal of many on the left.

But the strains of conservative thought Brooks himself embraced in his reaction to that failure - Burke and his successors - do rightly recognize that there is a wisdom in local knowledge that top-down plans for change need to respect and use in applying change in local circumstances. And part of that respect usually translates into occasional caution on the speed of change, since it’s hard to accommodate such local knowledge when change is too in a rush in too many different places at once.

As Brooks notes, there is “nothing intrinsically anti-government in Burkean conservatism” and many progressive goals are compatible with that inclination, even if the speed of change demanded by some on the left might be incompatible with a Burkean ethos.

But a political debate on the speed possible and tactics for making change is a quite different one from a fundamental debate on end goals of policy. A reluctance to move quickly on change can be cover for a defense of the status quo - but it also can be a proper Burkean resistance to ignoring local concerns and worries about the failures from the past of moving too quickly.

Some on the left fail to even try to distinguish between these two very different motivations - and may make enemies where they should be cultivating allies who just need convincing of the efficacy of the Left’s plans to then agree to speed up implementation of change- and who may actually have useful insights that might call for a slowing of policies that may be counterproductive if not implemented carefully.

Speed of implementation should not be a fetish on the left. Gradualism that steadily arrives at a goal in an effective manner may create far more lasting change.

There is rightful scorn for those like Brooks or Stevens or many others who stayed with conservative politics until the cancer of Trumpism made their mistake too obvious to deny. But in understanding WHY they got there in the first place, there is the chance for insight into the arguments progressives need to make to reach those who share similar ideological orientations.

And while a Burkean sensibility may seem to reinforce a more moderate policy approach than many on the left want, that may be true only of the speed of implementation but not the substance of the policy itself.

Brooks's repulsion to the debacle of how public housing was implemented is a telling example since that approach was a very liberal, technocratic program rejected by many on the left at the time as merely segregating the poor, while ignoring the broader needs of society at large. An alliance of the left with more Burkean elements would have resisted the destruction of urban renewal while possibly building a more long-lasting approach to address postwar housing shortages.

Whether the David Brooks of the world will end up finding alliances on the left or exclusively with more conservative elements in the Democratic coalition is an open question. But the trajectory of his very interesting essay doesn’t make the latter a foregone conclusion.