Build Public Banks as Response to SVB & Signature Bank Failures

Regulation is needed - but even better is an alternative to better support local businesses and communities

The big sell on the 2018 weakening of Dodd-Frank regulation for mid-size regional banks was the argument that costly regulation would just make it harder for community-focused banks to compete with the big banks- and if big banks expanded their reach, that would hurt local businesses overlooked by the “too big to fail” banks. (See this typical article at the time promoting that view.)

That turned out to be an excuse to let pretty large banks like Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and Signature loose without enough oversight. However, the core argument that we need financial institutions rooted locally that will invest for the long term in local communities is compelling.

However, many regional banks don’t take advantage of a lighter regulatory hand to better serve their local communities. Instead, they expand into new profit-making avenues, often on a global basis with aspirations of joining their larger bank brethren. Not only did SVB mostly serve just a narrow slice of tech-oriented startups in its California home base but extended that niche to a global network with branches in China, Denmark, Germany, India, Israel, Sweden, and the UK. Similarly, Signature became a national player in the crypto world as a main nexus for those wanting to connect their crypto funds to the regular banking world.

This is hardly the first time that banks that were supposed to serve regional interests went rogue, expanding into dicey ventures with an eye on national expansion. The multi-hundred billion dollar Savings & Loan debacle of the late 1980s had a similar trajectory.

Of course, there are institutions like credit unions rooted more tightly in the community, but most need the backstop of larger regional banking institutions to thrive. On top of the lack of support for many local businesses, the lack of a strong local banking sector across the nation means that 10% of the public lack any checking or savings account, and another 24% need to regularly use non-bank alternatives to pay bills, cash checks or purchase money orders. High fees mean the unbanked and underbanked paid $189 billion in fees and interest on financial products in 2018.

The North Dakota Public Banking Model

Enter the enthusiasm for public banking by many activists around the country. The idea is hardly new and not even untested. Public banking enthusiasts eagerly point to North Dakota, where the state has owned a bank, the Bank of North Dakota, since 1918 when the populist Nonpartisan League was in control of state government.

Its capitalization comes from the state government moving all of its own deposits from for-profit banks. Its primary mission is not to directly make loans but to support local banking institutions - and the result is that North Dakota has the most local banks in the nation per person (see graphic).

Groups like the Institute for Local Self-Reliance point to other benefits of the state runnings its own bank:

By buying up local mortgages and farm loans, it means local banks often don’t need to sell them to national and international banks, meaning roughly 25% of mortgage debts are held and serviced within the state.

The Bank acts as a mini-Federal Reserve, backstopping local banks through loans and support, helping keep many afloat during the 2008-2009 financial crisis.

The result is far more loans per capita to small businesses in North Dakota than in the rest of the country, over 400 percent more than the national average.

Having a state-run bank means when the federal government distributes low-interest loans, the Bank of North Dakota can take the lead helping distribute loans more effectively. During the pandemic, as the Washington Post wrote, due to the Bank’s support, “Small businesses there secured more PPP funds, relative to the state’s workforce, than their competitors in any other state.”

31% of the Bank’s loan portfolio are student loans, offering loan rates far lower than the national average (as low as 2% for many loans in recent years).

All of this while returning profits to the state- $385 million over 20 years or the equivalent of $3,300 per family to fund public services in the state.

As public advocates highlight in this graphic, the model of recirculating public funds within regions works quite differently in a public banking system than under our current approach.

Even before the SVB debacle, activists in California recognized regional banks were failing to serve much of the community and pushed for passage of AB 857 back in 2019, which began a process of allowing local governments to set up banks on the North Dakota model.

Los Angeles is considering setting up a local bank and projects that it would save local governments $100 million per year just in banking fees and interest paid by the government itself. As the graphic below highlights, the City has billions it could use to capitalize a local bank and use to support local businesses and communities, while actually generating revenue.

Public banking advocates also focus on the fact that public banking could radically cut the financing costs of borrowing money to build infrastructure projects like mass transit. Analysts estimate public banking could reduce 50% of those financing costs, which could eliminate an estimated $161 billion in annual interest payments that might otherwise substantially be going to infrastructure and human needs.

While the Bank of North Dakota does not encourage individuals to bank with it, California passed AB 1777 in 2021 to develop a plan to offer direct retail banking, including debt cards and direct deposit, through the public banks being established to support the unbanked around the state.

Consolidating Government Lending Programs: The Green Bank Model

The Bank of North Dakota is not of course the only example of local governments lending to local businesses. The reality is that states are involved in a range of banking-like activities through a myriad of loan programs, which have been increasing in recent years due to infusions of cash after the 2008 and pandemic recovery packages distributed funds targeted for such efforts. For example, the State Small Business Credit Initiative program was initially funded by the Obama administration and was reauthorized and expanded in 2021 with a combined $10 billion to states, D.C., territories, and Tribal governments to support small businesses loans.

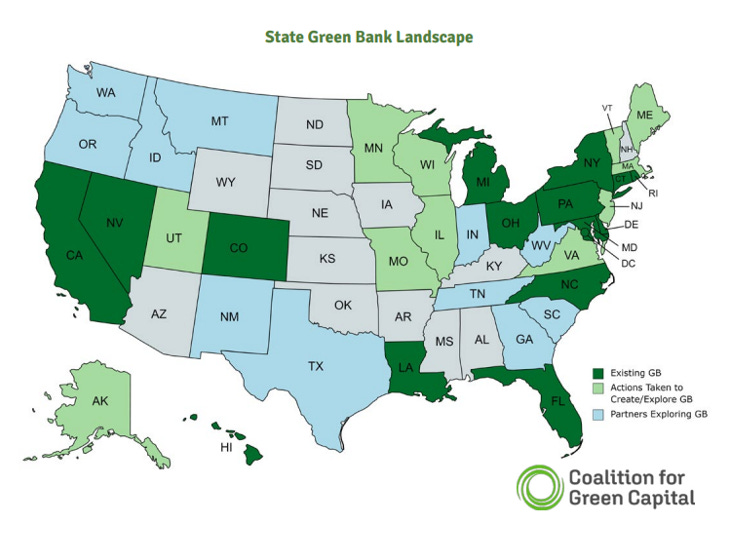

Most prominently, several states have been consolidating and expanding programs to fund green energy projects into what are being called “Green Bank” programs. By 2020, over $1.9 billion had been invested in state-level green banks, leveraging an additional $5.1 billion in private capital nationwide. Overall, there was still over $1.2 billion in remaining capital in those revolving funds by 2020 and that is likely to ramp up with new Biden administration investments via the Inflation Reduction Act. As this map highlights, green banks exist in many states across the country.

Connecticut’s Green Bank is considered to be the first Green Bank in the nation, having enacted legislation in 2011 to create a public agency that could coordinate a whole range of existing clean energy lending programs (see below) and help launch new programs to further the state’s green energy goals. While existing clean energy lending programs are done in current Green Bank states generally through private banking intermediaries, these functions could easily be incorporated into a North Dakota-type public bank, creating additional cost savings for the public.

Green energy projects are especially suited to public banking since they often involve a nexus of government action and long-term investments by individuals and businesses. A popular example is PACE - Property Assessed Clean Energy programs - where individuals and businesses get loans for adding solar or energy-saving upgrades while paying off loans through surcharges on their property tax bills, delivering essentially free installation at no upfront or net monthly cost for property owners. Active PACE programs exist in more than 30 states and from 2009 to 2022, there have been 2,900 commercial PACE projects with over $4B of investments and 323,000 home upgrades involving $7.7 billion for residential PACE projects. Since the government is already largely backstopping lending in these projects, it can save public funds by cutting out the middleman and making the loans directly itself.

A range of other programs - from Clean Energy Revolving Loan Funds to what are known as Power Purchase Agreements - where governments lease building space to deploy clean energy infrastructure - all represent ways state governments are involved in and can expand their lending activities.

Lessons from SVB and Signature: Build Public Banks to Support Regional Banking

We have now gone through multiple cycles where the breakdown of regional banking has been a prime cause of those crises, first with the crackup of the Savings and Loan system in the 1980s, then the financial meltdown of 2008-2009 - driven by local mortgages being sold off and securitized by international banks - and now the SVB and Signature Bank failures.

Private banking has an imperative to expand profits for their shareholders, not serve the community, so private banks will invariably abandon support for local businesses, especially those who need it most, in favor of the greener pastures of higher-profit enterprises, whether venture capital firms or crypto businesses as with the recent examples.

Expecting private banks to serve a public policy goal of supporting regional banking and local economic development is a proven policy failure at this point.

At the same time, there are proven examples of public banking success, the Bank of North Dakota being the obvious example, but a whole myriad of local lending programs by governments being the other.

Consolidating all of these approaches into a vibrant public banking system across the nation should be the obvious response to the recent SVB and Signature bank failures. From every indication, it would better serve local small businesses and the unbanked, while saving taxpayers money.

Only the greed of the banking lobby should stand in the way of getting it done.

I worked in a regional in the late 90s when I first went in-house. As I became tuned in what struck home was the bedrock model--the payment franchise. People need banks to get money in and send it out. As a bank, you took it in as cheaply as possible by paying teeny interest on deposits and trying to offset those with a swarm of tiny fees. And you worked hard to make your part in sending it out in the form of currency disbursal and check clearing as efficient as possible.

As a result, you can leverage the float, the average balance that your customers maintain, to lend out for various purposes. Home loans come to mind, but that's a misdirect. Even then very few banks were "portfolio lenders." They originated loans and sold into Fannie/Freddie and maybe Ginnie and the jumbos they sold into mortgage backed securities. Through perfectly legal accounting smoke and mirrors they money that they would receive for administering the loans on behalf of the new owners could be taken into income immediately as a capital asset.

Middle market commercial loans of heft were syndicated with the lead bank maintaining the lead and a group of participating banks funding the loans and receiving proportionate payments of interest and principal.

Big customers cut custom deals across Wall Street.

We all know how credit card lending works. Hook 'em in with zero-interest transfers and then bleed dry with 29% APR for life.

Otherwise whether in the form of signature loans, auto loans or the host of bank lending services that the vast majority of people draw on, banks primary operate at the wholesale level.

The picture of community banks as pillars of the community is broadly overdrawn. Leading to my question: do we need to keep encouraging reliance on free deposit funding of banks who are primarily operating as capital market middlemen?

No.

We can argue about that separately, while I help kick the leg out of the other rationale for retail banking--paychecks and bills.

The marginal cost of processing ordinary transfers of credits and debits is so close to zero that it is not worth measuring. For the Boomers and the drug dealers and other criminals who still rely on currency they can be served by ATMs--you don't have to be a bank to operate one. Everyone else can use an app.

There are a lot of platforms available to run a transaction clearing table. My candidate is an ACH bulked up to handle the volume. Let its costs be recouped by a penny tax (or a nickel or whatever) on transfers below $10,000 (that's the current threshold for tracking nefarious money transfers) Let a thousand re-sellers bloom to provide value-added services such as custom ringtones when you get money in. Let the Treasury use the float for reducing the amount of receivables financing debt it has to issue. In theory, taxes could be lower.

So, where's the money going to come from for lending if there's no free float?

That's the best part--from capitalists. From the tiny fraction of the population who lack the elan to blow out tens of billions of dollars on vanity project but who hoard assets against the day that there bragging rights might take a hit.

I propose a tax on inert capital frozen into non-circulating assets coupled with a reasonably favorable tax treatment on income from retail lending.

Let the games begin.

EIGHTEEN PUBLIC BANK BILLS WERE INTRODUCED IN 2021

https://publicbankinginstitute.org/